In 399 CE, Faxian — a monk in China’s Jin Dynasty — went on a pilgrimage to the Indian subcontinent to collect Buddhist scriptures. Returning after 13 years, he spent the rest of his life translating those texts, profoundly altering Chinese worldviews and changing the face of Asian and world history.

Faxian illustrated as visiting the Palace of Asoka in 407 CE, in modern-day Patna, India, in the 19th century English book series, Story of the Nations.

After Faxian, hundreds of Chinese monks made similar journeys, leading not only to the spread of Buddhism along the Nirvana Route, but also opening up roads to medicine men, merchants and missionaries.

Along with the two other great translation movements — Graeco-Arabic in the Umayyad and Abbasid periods (2nd-4th and 8th-10th century) and Indo-Persian (13th-19th centuries) — these events were major attempts to translate knowledge across linguistic boundaries in world history.

Transcending barriers of language and space, acts of translation touched and transformed every aspect of life: from arts and crafts, to beliefs and customs, to society and politics.

Going by the latest casualty in the heated — but necessary — debates around representation in our creative and cultural arenas, none of this would be possible today.

Last month, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, the youngest writer ever to win the International Booker Prize for The Discomfort of Evening (with translator Michele Hutchison), was chosen to translate 22-year-old American poet laureate Amanda Gorman’s forthcoming collection, The Hill We Climb, for Dutch publisher Meulenhoff.

Gorman selected Rijneveld herself. But amid backlash that a white prose writer was chosen to translate the work of an unapologetically Black, spoken word poet, Rijneveld resigned saying,

I understand the people who feel hurt by Meulenhoff’s choice to ask me […] I had happily devoted myself to translating Amanda’s work, seeing it as the greatest task to keep her strength, tone and style. However, I realise that I am in a position to think and feel that way, where many are not.

This week, meanwhile, the poem’s Catalan translator Victor Obiols told AFP he had been removed from the job by Barcelona publisher Univers.

They did not question my abilities, but they were looking for a different profile, which had to be a woman, young, activist and preferably black.

We live in a world rife with controversies around cultural appropriation and identity politics. The power differentials created by the twin forces of colonialism and capitalism are being interrogated in every realm today.

It was only a matter of time before these burning issues ignited the art of translation.

Usually invisible and taken-for-granted, acts of translation take place around us all the time. But in the field of literary translation, questions of authorial voice and speaking position matter.

Marginalised creative practitioners and their growing audiences assume importance in a global publishing regime controlled by a dominant minority wielding majority power over issues of representation.

So it is fitting that some have drawn attention to the myriad spoken word artists eminently qualified to undertake translation in the Netherlands. And Dutch agents, publishers, editors, translators and reviewers could certainly broaden their horizons and embrace diversity.

Nevertheless, if humans only translated the familiar, how would we ever have an inkling of the astonishing world out there that is not familiar?

The task of literary translation entails grappling with profound difference, in terms of language, imagination, context, traditions, worldviews.

None of this would enter our quotidian consciousness but for the translators who step into uncharted waters because they have fallen in love with another tongue, another world.

Translation is resistance

Translators ferry across the meaning, materiality, metaphysics and all the magic that may be unknown in the mediums and conventions of their own tongue. The pull of the strange, the foreign, and the alien are necessary for acts of translation.

It is this essential element of unknowingness that animates the translator’s curiosity and challenges her intellectual mettle and ethical responsibility. Even when translators hail from — or belong to — the same culture as the original author, the art relies on the oppositional traction of difference.

Through opposition and abrasion, a creative translation allows for new meaning and nuance to emerge.

Noaki Sakai, a Japanese historian and translator at Cornell University, writes about the historical complexity of this process. The practices of translation, he says, are “always complicit with the building, transforming and disrupting of power differences.”

Translation is domination

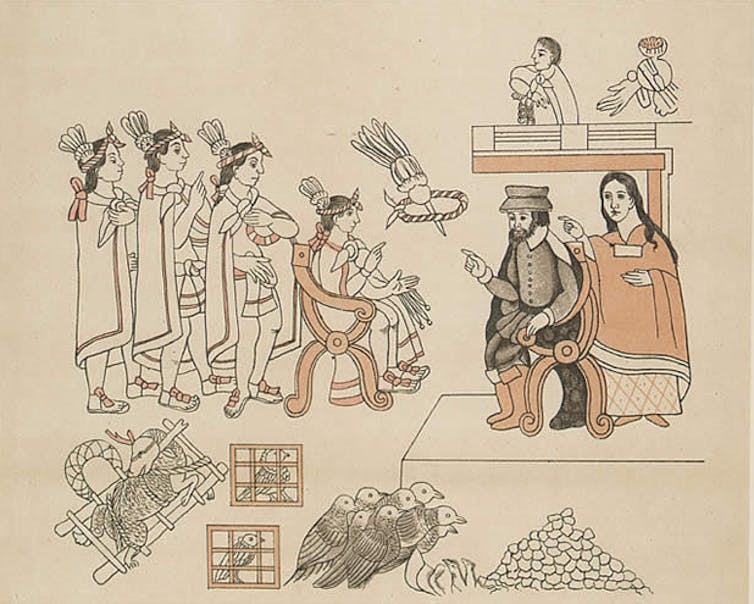

Translation has, however, been a tool for domination in colonisation. La Malinche, for instance, acted as an intermediary and interpreter for the conquistador, Hernán Cortés, in the 16th century Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire.

In this drawing by an unnamed Tlaxcalan artist c. 1550, La Malinche (far right) is acting as translator between Hernán Cortés and Moctezuma II, the ninth ruler of the Aztec Empire. Bancroft Library, UC Berkley

Patyegarang was Australia’s first teacher of Aboriginal language, to early colonist, William Dawes, and crucial for the survival of the Gamaraigal language in Eora country. At 15, and as an initiated woman, she was Dawes’ intellectual equal, learning English from him and negotiating a relationship of mutual translation while holding on to her own cultural legacy.

In each of these cases, European imperialists learnt how to survive the lands they were conquering through the processes of translation. Moreover, they used the same languages to fabricate the story of their own superior Western civilisation, at the cost of Indigenous cultures.

As translation theorist Tejaswini Niranjana explains, translation:

shapes, and takes shape within, the asymmetrical relations of power that operate under colonialism.

Translation is not a neutral activity. It functions in a complex set of socio-political relations, where parties have vested interests in the production, dissemination and reception of stories and texts.

Academics Sabine Fenton and Paul Moon have written about the deliberate mis-translation of the Treaty of Waitangi, a strategic example of colonial omissions and selections that achieved “the cession of Maori sovereignty to the Crown.”

One egregious interpolation was the replacement of the word mana (sovereignty) with kawanatanga (government), which misled and induced many Maori chiefs to sign the treaty.

In situations of conflict and war — and the displacements that result from them — translation again becomes a weapon privileging the powerful, as seen in the impenetrable bureaucratic paperwork, in the dominant language, governing asylum and refugee seeker decisions.

In this charged context, the case of Gorman and Rijneveld becomes a lightning rod for addressing historical disempowerment and injustices.

Translation is diplomatic

In the absence of a level playing field for writers to have their voices heard in the global publishing market, there does need to be historical awareness and post-colonial sensitivity.

To Rijneveld’s credit, this sensitivity has been demonstrated. After stepping down as Gorman’s translator, they composed a poem:

never lost that resistance, that primal jostling with sorrow and joy,

or given in to pulpit preaching, to the Word that says what is

right or wrong, never been too lazy to stand up, to face

up to all the bullies and fight pigeonholing with your fists

raised, against those riots of not-knowing inside your head

Still, while representation is the moral imperative of the 21st century, it is my modest proposal that in the realm of literary translation, the pull of the unknown and the unfamiliar is one of the most important truisms: Rijneveld’s “riots of not-knowing.”

Already the world is losing a language every fortnight; 7000 languages are expected to be extinct by the end of this century. Yet it has often been argued that linguistic diversity is an indicator of genetic diversity, the latter being critical to the survival of the species.

If humans only translate what is known within their own four walls, or what is familiar to them within the boundaries of their own imaginations, something essential is lost both to translation — and to the profligate tongues that proliferate our humanity.

Translation is activism

We do not live in a post-racial world. We do not live in a borderless world — as brought to the fore powerfully by the COVID-19 pandemic. For translators in transnational times, it is of the essence that we break down ethno-linguistic borders, accepting the challenge of the confronting.

In my own work, I have collaborated on translations of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander, and tribal & Dalit Indian poets. This has necessarily involved the hard work of understanding historical incommensurabilities.

Yes, structural inequalities mount by the day in the face of capitalism, which is a faithful handmaiden to the ongoing machinations of colonialism. Translators do not live in a vacuum. We are not immune to the forces of structural racism.

But why is it that Rijneveld had to renounce the commission as an individual? Why does this recent story become about individual actions, rather than the entrenched patterns of operation of publishing houses like Meulenhoff?

To achieve equity, transformation must be structural — it cannot fall on the shoulders of one translator alone, making them a fall guy for the business of books as usual.

The directors and CEOs of dominant global (read: Western) publishing companies are predominantly white. Which begs the familiar question: what if editorial boards reflected the multiplicity of society across the axes of class, gender, race, sexuality and ability?

Imagine the scenario if even one of Australia’s mainstream publishing houses was led by a non-white head and/or board?

It is precisely the duty of heads of publishing houses, literary and review magazines and cultural institutions, to invite a teeming world of translators to take charge of what needs to be done.

The biblical story of the Tower of Babel, painted here by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in 1563, tells of how all of humanity once spoke one language and tried to build a tower to Heaven, before God acted to make the people unable to understand each other, and unable to collaborate. Kunsthistorisches Museum/Wikimedia Commons

Still, a translator must attend to the demands of integrity and imagination as much as the demands of history and society. She must throw herself into the challenging task of being in another time and place, of rubbing against the grain of her own aims and assumptions.

Only in imagining such a Babelian world of difference can a truly radical set of possibilities become alive.

This is not to argue that translators who come from similar backgrounds will not be able to engage in the task of translation in ways that wrestle with the creative resistance entailed in such a task. But the field must remain open to whoever is called to the task.

Literary translation is often a matter of happy accidents and passionate engagements. Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (2007) became a runaway success in the United Kingdom and United States in 2016, when Deborah Smith, who had been learning Korean for only six years, embarked on the task.

There have been critiques of her translation, but representation is not the issue. Part of the beauty of translation is that texts can be critiqued, and translated again and again.

Translation lore is enriched continually by examples of re-translations, such as the ten translations into English of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina alone, or the two of Orhan Pamuk’s The Black Book.

The act and the art of translation requires the permission to transcend borders, the permission to make mistakes, and the permission to be repeated, by anyone who feels the tempestuous tug, and the clarion call, of the unfamiliar.

To rein in such liberty through categories and compartments that imprison our creativity is a disservice to the human imagination.

So let a thousand translations bloom: that would be a start and not an end to translation as we know it now.